You don’t go to work at the General Electric plant in Waterford, New York, without knowing it could have an impact on your health. You need hazmat training, fireproof clothing, special footwear, you name it.

When a routine doctor’s visit discovered something that turned out to be cancer, electrician Jack Mack, at what’s now the Momentive Performance Materials plant, took the news in stride. For decades, his union had advocated for and won great health care.

“We work with chemicals…carcinogens,” Mack said. “We understood the risks, but we also knew the company had our back. We chose to work here.”

The hazards are serious, which means Mack and his fellow union members maintain incredibly high standards for safety and protection. He works in the plant’s waste treatment facility. Volatile and flammable solvents and chemicals are handled in the area. Much of what he installs has to meet a classification known as “explosion proof,” and then there is always the potential for leaks. Electrical equipment can create an ignition source.

Mack followed his father into the plant 39 years ago, in the midst of GE’s industrial dominance.

Nearby GE plants employed as many as 40,000 workers, on par with the largest factories in the United States, so big they had full internal transportation services with fleets of buses and drivers like any mid-sized town or small city. The Momentive plant was never so large, topping out with some 2,000 workers in its heyday. But GE still had a massive presence in this part of upstate New York.

“I was always proud to work for General Electric. The company wasn’t warm and fuzzy, but it stood behind what it said,” Mack said.

It’s hard to grasp the extent of the change between then and now.

When GE sold the plant in 2006 to Apollo Global Management, the private equity firm based in New York City claimed nothing would change, but after just a few months they slashed the pay of the less-specialized workers. Then, about three years ago, the company froze the pensions of everyone younger than 50. Last year, the new owners went after the health benefits of workers and retirees with the initial 2016 contract negotiations.

It was a shocking proposal. Instead of the kind of health care that gave Mack and his colleagues the peace of mind necessary to work in a toxic environment, they faced a high-deductible plan for current employees and nothing at all for retirees, except a little financial assistance to help pay premiums for the contract’s first year. Otherwise, the retirees would simply be dumped into a private health insurance exchange.

“We’ve got people with long-term exposure to hazardous materials. If you’ve had these exposures, you’d better have good health care. If you’ve got a high deductible, you’d better have enough money in the bank to take care of it, because you’re going to have a problem,” said Mack.

The workers rejected that contract by a vote of 95% and went on strike on Nov. 2. That first day, on the picket line, New York State AFL-CIO President Mario Cilento gave the striking workers a rousing speech, and the support from the community and other labor unions that followed was powerful.

In the end, the company budged enough to end the strike, but it was a frustrating struggle. The workers held their own and proved a point, but retiree health care was lost. That hurts. The local union won a lump sum payment for new retirees and a few other measures, but the table was set for more fights in the future. Still, Mack feels the workers are ready for it.

“We sent the company a message,” he said, acknowledging that there are no winners in a strike. “They pushed too far. So we stood up. And if necessary, we’ll do it again.”

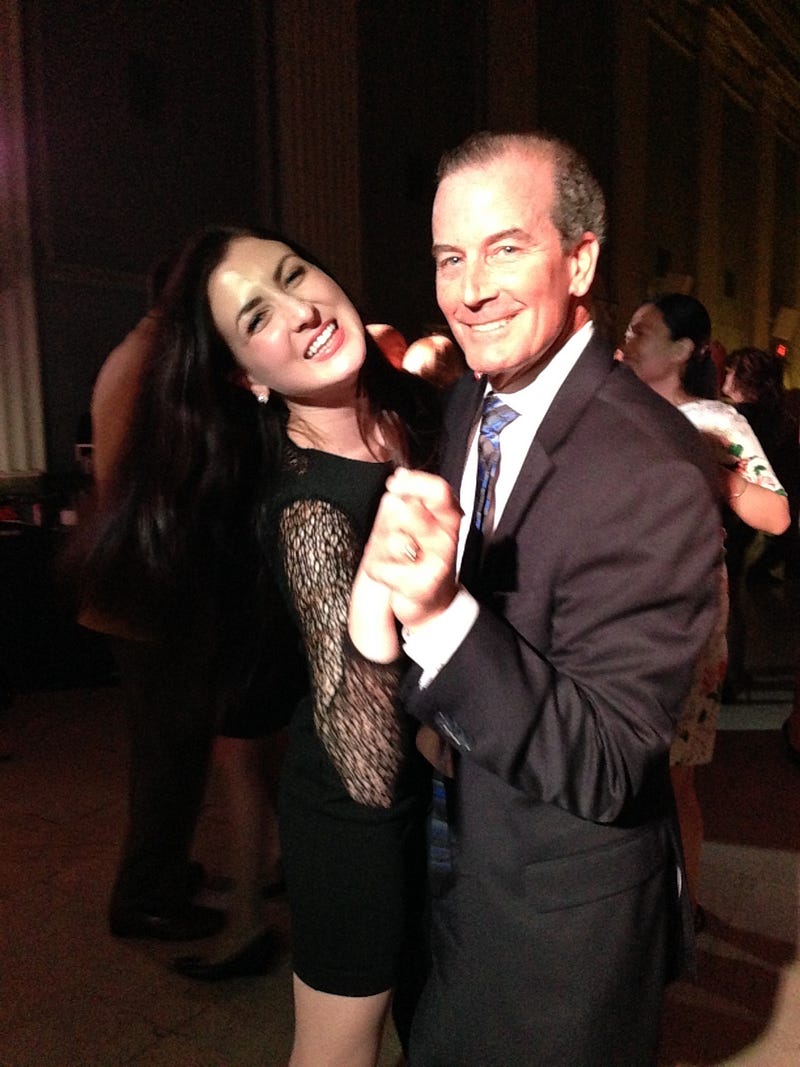

Nobody spends a whole life working. “When we go to parties, he is rarely off the dance floor,” says Jack Mack’s wife Erin. In this photo, Jack is dancing with daughter Emily, a recent graduate from Bucknell University.