History has long been portrayed as a series of "great men" taking great action to shape the world we live in. In recent decades, however, social historians have focused more on looking at history "from the bottom up," studying the vital role that working people played in our heritage. Working people built, and continue to build, the United States. In our series, Pathway to Progress, we'll take a look at various people, places and events where working people played a key role in the progress our country has made, including those who are making history right now. Today's topic is the Pittston Coal strike of 1989.

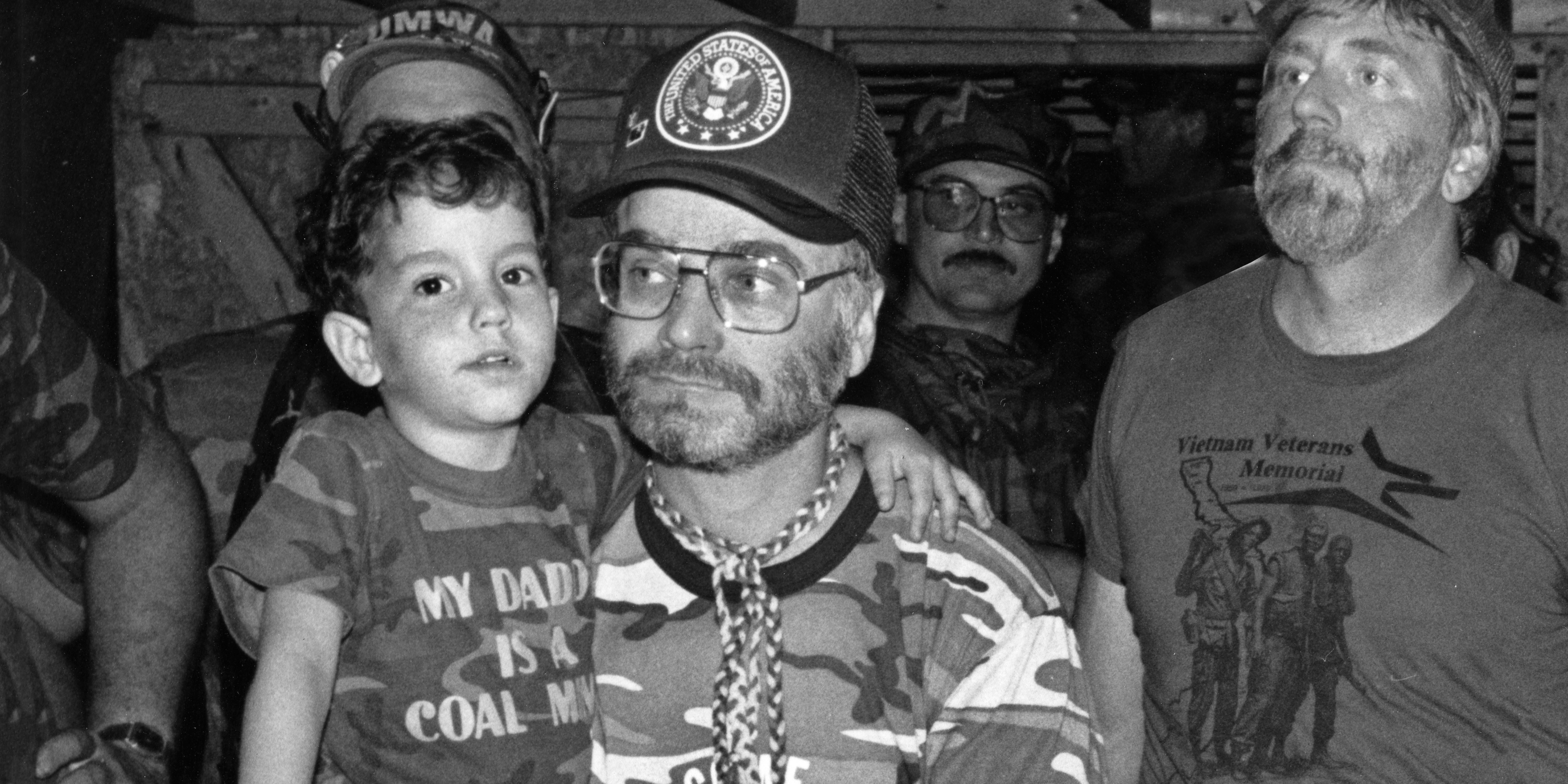

One of the most monumental strikes in U.S. mining history was the Pittston strike that started in 1989. More than 50,000 people took part in strike-related activities in 11 states, most importantly in southwest Virginia.

In the late 1980s, the Pittston Coal Company was the largest exporter of coal in the United States. In February 1988, the company informed the miners, members of the Mine Workers (UMWA), that they were taking away retirement and health benefits. Considering the relative dangers of mine work, the workers rejected the changes, which meant they couldn't support their families if they were injured while working.

In April 1989, then-UMWA President Richard Trumka called a selective strike against Pittston. Some 1,700 miners from Virginia, Kentucky and West Virginia went on strike. The strike lasted nearly 11 months and the key turning point was the takeover of Pittston's Moss 3 plant by UMWA members. Moss 3 was the third largest coal preparation plant in the world at the time and central to Pittston's operations. The takeover was a last resort, as the miners believed they couldn't win without being more active in securing a victory.

A well-coordinated effort led to a four-day takeover of the plant that was widely supported by the local community. At one point, members of the community provided a human wall around the plant to prevent arrests. This changed the tenor of the negotiations because it was a direct challenge to Pittston and it shut down the company's coal production in Virginia for nearly a week.

A key part of the Moss 3 action was "Camp Solidarity," set up only a few miles from the plant. The camp opened in June, with a gathering of more than 1,000 people, and it became a place to house and feed strikers and visitors. On many days, the camp would feed more than 2,000 people. As a symbol of community support and solidarity, the camp also boosted morale among strikers and raised money to support strike funds.

In the broader community, many restaurants and stores refused to serve state troopers who were arresting strikers. Students engaged in walk-outs, wearing camouflage in solidarity with the miners.

“All the power that Pittston thought they had sort of evaporated when those communities and those church groups and civic groups and community groups and schools and students all came around to support us on the issue,” Trumka said.

On February 20, 1990, 63% of the striking miners voted to ratify a new contract that ended the strike. Upon the signing, then-UMWA Vice President Cecil Roberts said: “I hope we can bring peace back to Southwest Virginia and let people get on with their lives. I hope the future is now in our hands.”

The strike was one of the longest and largest acts of civil disobedience in recent decades. It united not only the people of southwest Virginia, but the broader labor movement. The UMWA and the local community set the modern template for how to protect the rights of working people.

Roberts, now the president of the UMWA, spoke to the importance of the Pittston strike: “Labor winning here, I think, helped to turn things around for the entire labor movement. The labor movement was in dire need of a victory, the UMWA was in dire need of a victory. The union members were fighting for their own jobs and a way of life....People understood that if you fill up the jailhouses and fill up the courthouses, then sooner or later you’ll get someone’s attention. Soon we got the attention of the judges, and soon we got the attention of the governor, and soon we got the attention of the president of the United States, and he sent the secretary of labor down to the coalfields.”

The biggest upside of the strike, Roberts said, was the passage of the Coal Industry Retiree Health Benefit Act of 1992, which extended benefits to union miners whose employers were no longer in business. Without the strike, that law wouldn't have passed.

Watch these videos from UMWA to learn more.

30th Anniversary of the Strike:

UMWA President Cecil E. Roberts:

William McCoy, UMWA Local 1259:

Harless Mullens, UMWA Local 2274:

Willard Dingus, UMWA Local 1259